Summary

Can we design a system that promotes fairer prices on markets with personalized pricing? In our last study, we found evidence that prices of flights and hotels do really vary based on users’ browsing history. If consumers want to ensure that they’re getting the best price possible, what options do they have?

Consider a scenario where you and your friend are shopping online for the same pair of shoes. Your friend searches and finds the shoes for $100 while you see it for $110. You would probably ask your friend to buy the shoes for you and pay them back. If instead of your friend, this were an anonymous fellow shopper, you might pay them back $105 to compensate them for their time. This idea led us to design an exchange system that could be used to help consumers find the lowest price possible for a given item, while promoting reasonably fair outcomes.

What we did

To assess the feasibility of such a system, we designed an agent based model to understand how implementing that system would affect pricing outcomes. The design of our exchange system relies on matching pairs of participants (“buyers” who are seeking lower prices, and “intermediaries” who are able to buy items at lower prices) who will accept the trade if both benefit. These matchings are proposed based on the system’s fairness goals—in our work we tested 4 such measures. Further, we consider two methods by which the price of the exchange can be set: by individual negotiations, and system-determined transaction prices. Using these guiding principles, we examined which fairness objectives and matching procedures could best facilitate fair prices.

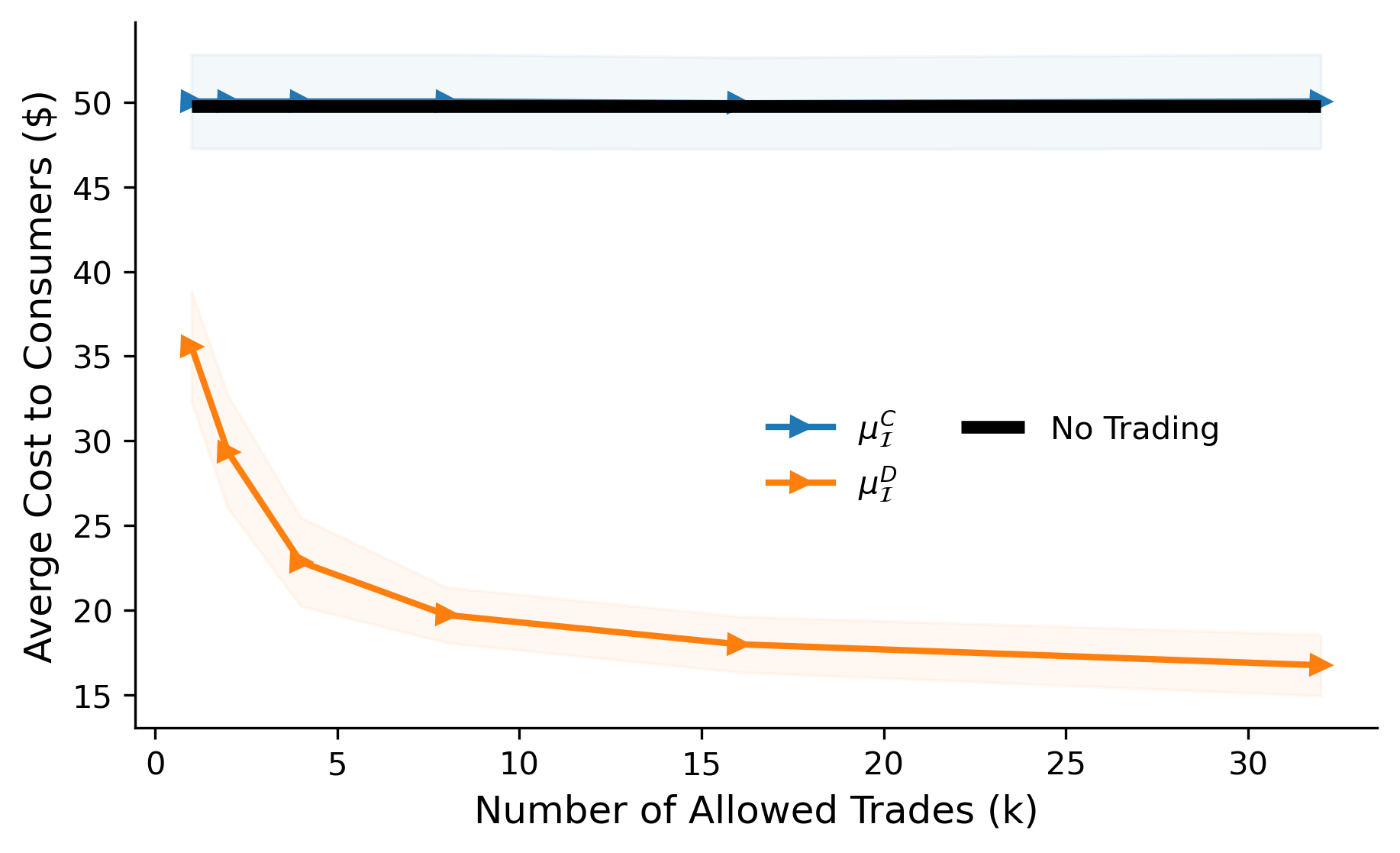

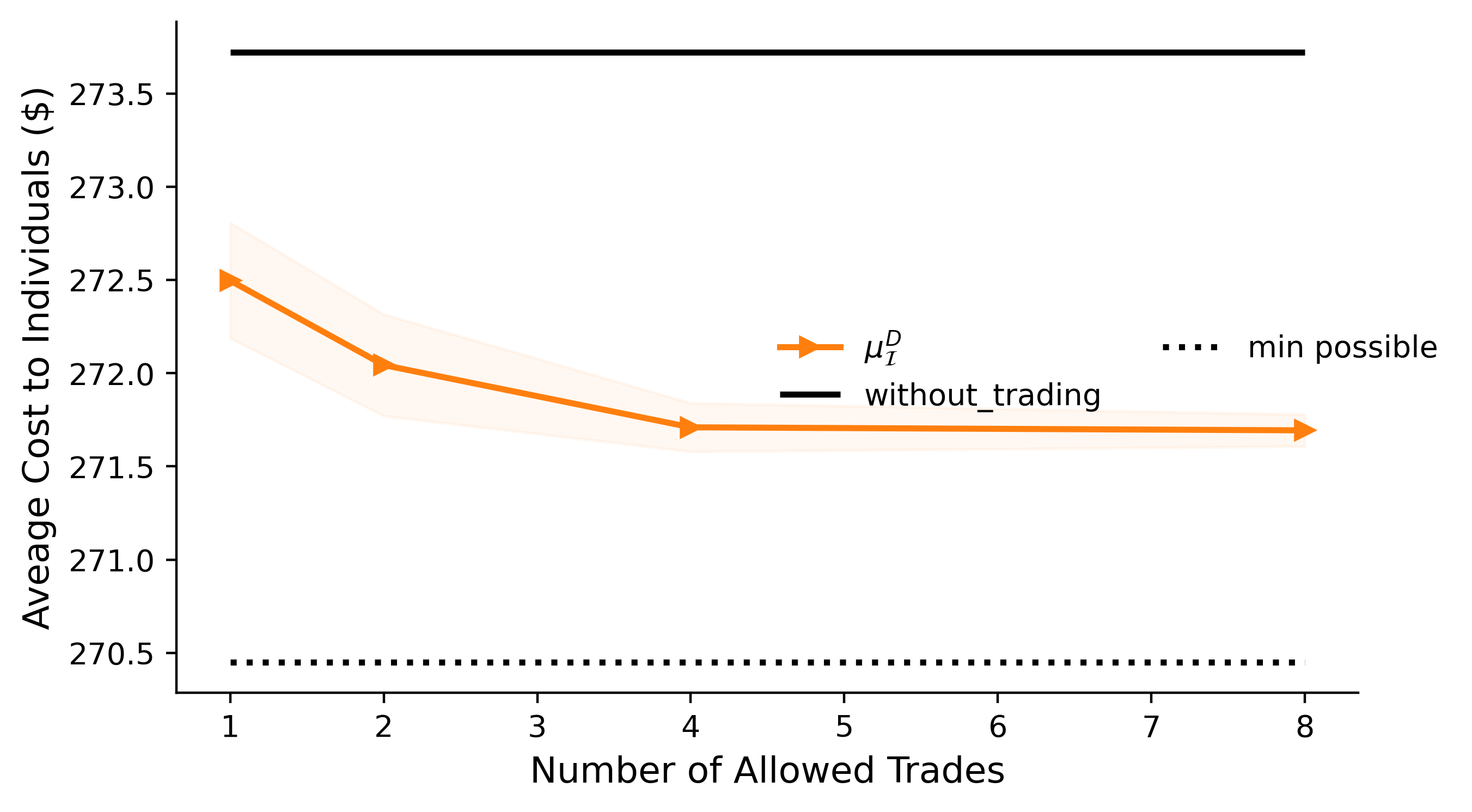

While the decentralized (individually negotiated) prices prove successfully fairness-improving, we find that centralized price setting results in little change. Below we show the change in fairness metric for decentralized (orange) versus centralized (blue) price setting, and compare this to a baseline of no trading (black). We vary on the x-axis the number of trades agents are allowed to engage in. We see when our fairness metric aims to achieve low average prices, decentralized price-setting is able to reduce prices while centralized is not. The lack of success for the centralized matching procedure is due to the exchange system being unaware of consumers’ private utility functions, so it presents consumers with transaction prices that do not benefit both parties, and thus very few trades occur.

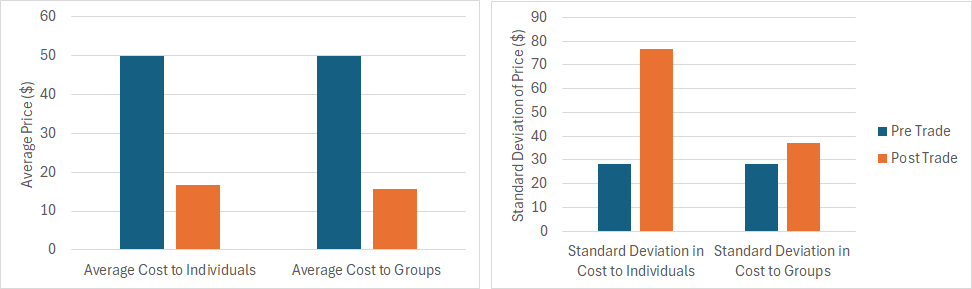

Focusing on decentralized price-setting, we further examine how this pricing scheme affects our four different fairness optimization metrics. We find that while decentralized matching can improve fairness in terms of minimizing prices people pay, it actually increases the standard deviation of prices paid. This is because while a buyer agent may only profit once in our simulation (they need only buy one unit of the good), an intermediary agent can profit a number of times. In the decentralized setting, therefore, the agent acting as an intermediary can engage in more beneficial trades.

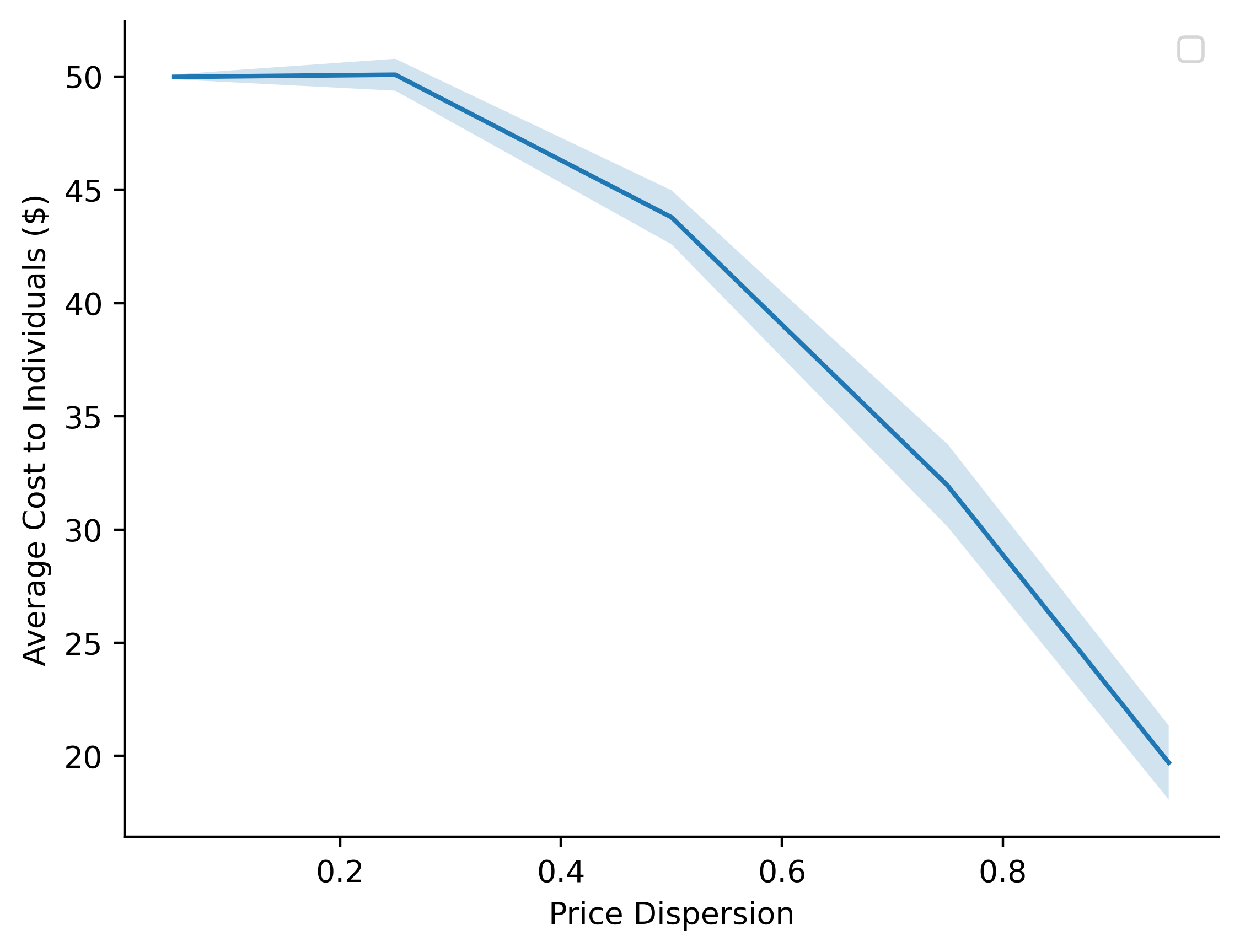

We also explored how different pricing regimes may affect the ability of the exchange system to promote fair pricing. In particular, we examined what happens when prices in the original market are widely spread out (or dispersed) compared to when prices are more clustered together. At a high level, we defined dispersion as a value between [0, 1], where low dispersion means most prices are concentrated around the average, while high dispersion means there are more prices seen at the extremes (see full paper for more in depth measurement). We found that the exchange acts as a counterbalance against widely dispersed prices. In this setting, there is more incentive for those with access to lower prices to benefit by acting as intermediaries to consumers who have higher prices. Counterintuitively, this actually can help drive the average price down further compared to a scenario where everyone initially receives the same price.

Putting this all together, what does it mean? We find that an exchange system driven by individual negotiations by consumers can lead to fairer prices in markets with a high degree of price personalization. In this way, our system can serve as an effective counterbalance to personalized pricing.

After exploring results on our simulated pricing distributions, we then test how this might play out with a more realistic pricing distribution—in particular, the flight prices we found in [cite]. We consider the case where some consumers have access to lower prices, and can serve as intermediaries multiple times (1-8 times). With this more narrow pricing distribution, we find that this exchange can reduce prices by an average of $1-$2. This might not seem like a lot in the grand scheme of things, however, given that this is the savings for a single transaction, repeating this process can lead to potentially larger savings over time.

Continuing from here

In short, we demonstrate the utility of an exchange-driven system in reducing the impact of personalized pricing, showing that trading can act as a counterbalance to extreme personalization. A system such as this one could also help consumers become more aware of some black-box mechanisms online that they hadn’t considered before—consumers currently could be seeing drastically different prices for the same items and be completely unaware! This awareness of the pricing landscape, and a mechanism to enable trading, can help people make informed decisions regarding what they consume—ensuring they are treated fairly and getting the best outcomes for themselves.