Summary

Why do online conversations, especially those involving journalists, so often descend into toxic, coordinated attacks?

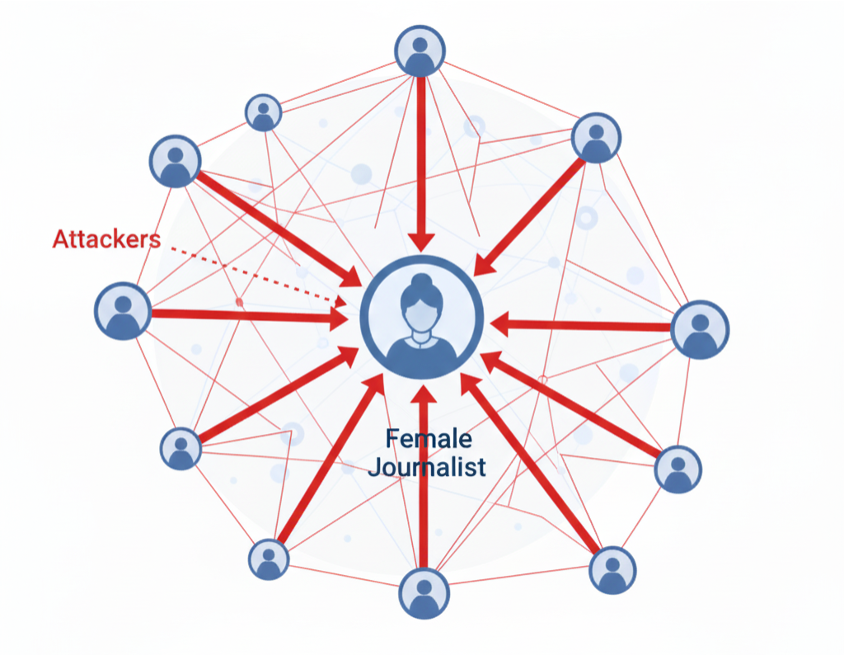

Targeted harassment against vulnerable groups, particularly female journalists, is increasingly common on social media. This creates a well-documented “chilling effect,” where coordinated attacks silence voices and discourage participation.

Identifying this behavior is incredibly difficult for two main reasons:

- Complex Structure: Online conversations aren’t linear lists; they are complex, branching trees of replies.

- Hidden Strategies: The strategic coordination driving user behavior—who to reply to, when, and with what content—is hidden from view.

In our paper, presented at CSCW 2025, we introduce ConvTreeTrans, a novel tree-structured Transformer model designed to tackle this problem. Our framework can jointly identify distinct user groups (attackers, supporters, and bystanders) and, for the first time, discover their hidden, composite strategies.

What we did

First, we built a large-scale dataset by collecting over 3 million tweets and replies from 2018 to 2022. This data was centered on 13 high-profile female journalists from diverse cultural backgrounds (US, China, India, UK, Pakistan, etc.).

Next, to create our ground truth, we manually annotated thousands of replies, categorizing them into three distinct groups:

- Attackers: Replies that are toxic or contain personal attacks on the journalist.

- Supporters: Non-toxic replies that align with the journalist’s viewpoint.

- Bystanders: Non-toxic, on-topic but neutral replies, or toxic replies not directed at the journalist.

| Role | Example Text | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Attacker | "Are you pretending to be a cultural person again? Do it all day, are you tired?" | Contains a sarcastic, mocking tone that targets the journalist personally. |

| Supporter | "What a terrific quote! Thank you for sharing with us " | Positive and supportive of the journalist’s post, without toxicity. |

| Bystander | "Dead on. Now I’ll never get it out of my head." | Neutral comment without clear alignment or attack, making it a bystander response. |

Our key insight is that to understand a reply’s role, you must understand its context within the entire conversation tree.

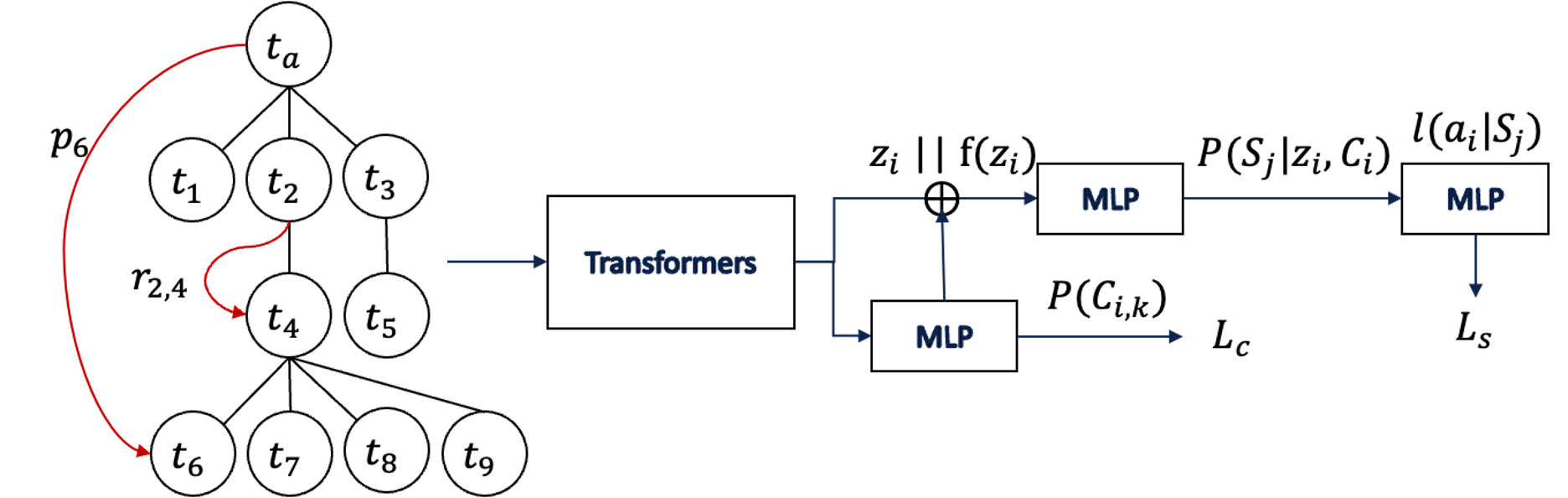

We developed ConvTreeTrans, a Transformer model that analyzes the hierarchical structure of these conversations. Unlike standard models, ConvTreeTrans incorporates both:

- Global Path Information: Where is this reply in the entire conversation (e.g., its depth)?

- Local Path Information: Who is it replying directly to (its parent)?

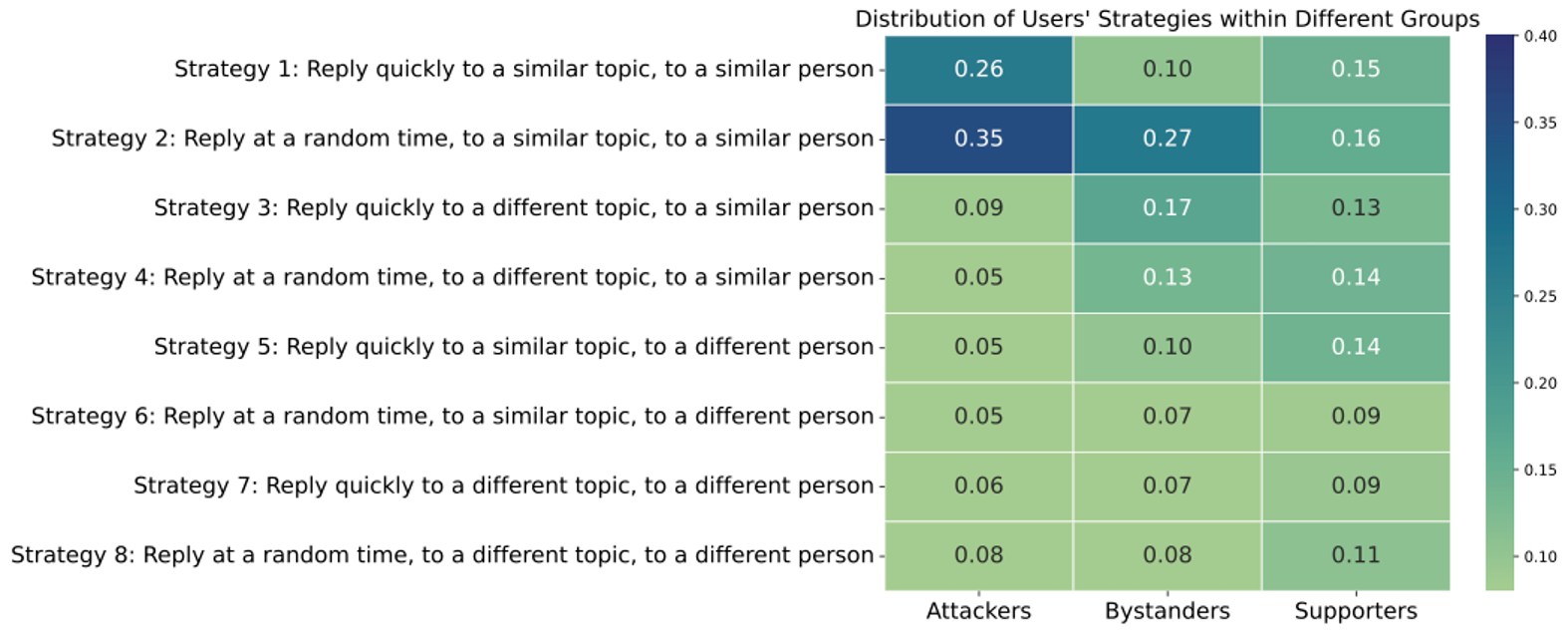

Finally, we used this model to identify 8 composite strategies based on three key aspects: People (replying to similar/dissimilar users), Topic (replying to similar/dissimilar topics), and Time (replying quickly or at random).

What we found

Our analysis answered four key research questions with several striking findings:

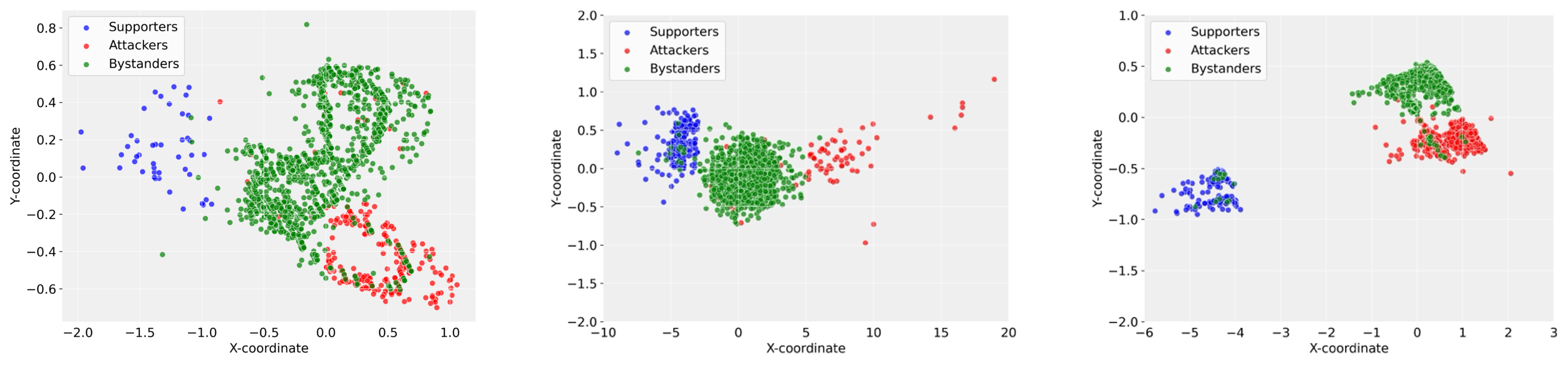

- Our Model Works (RQ1): ConvTreeTrans successfully classifies user groups with 82.15% accuracy, significantly outperforming prior methods that fail to properly model the conversation’s tree structure.

- Attackers Are Coordinated; Supporters Are Not (RQ2): This was our most significant finding. Attackers strongly prefer specific, coordinated strategies. Their two most common strategies are “Reply quickly to a similar topic, to a similar person” (26% of the time) and “Reply at a random time, to a similar topic, to a similar person” (35% of the time). In sharp contrast, supporters show no clear strategic approach. Their engagement is diffused, spontaneous, and uncoordinated.

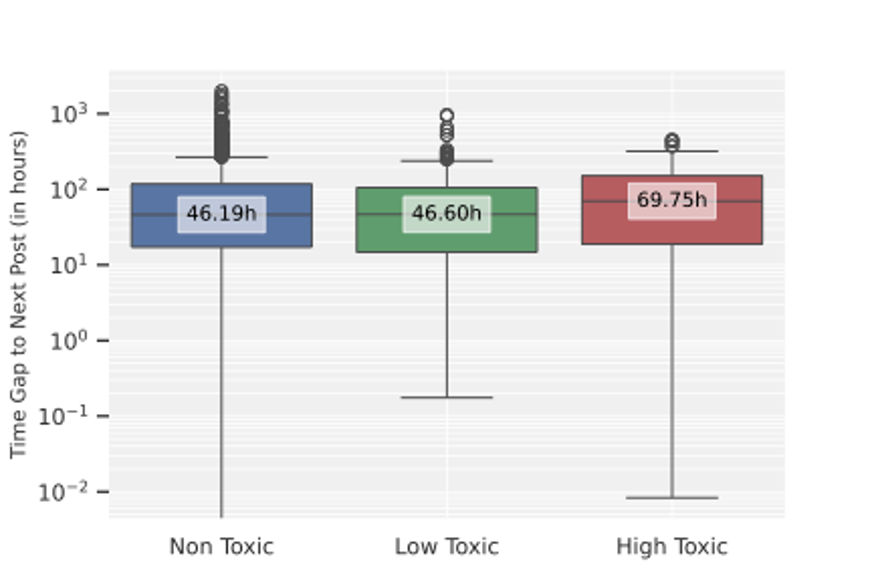

- The “Chilling Effect” is Real and Measurable (RQ3): We found a strong correlation between online attacks and a “chilling effect” on journalists. After receiving a high proportion of toxic replies, journalists significantly delay their next post—by a median of approximately 23.5 hours (the difference between the median gap in non-toxic environments, 46.19h, and high-toxic environments, 69.75h).

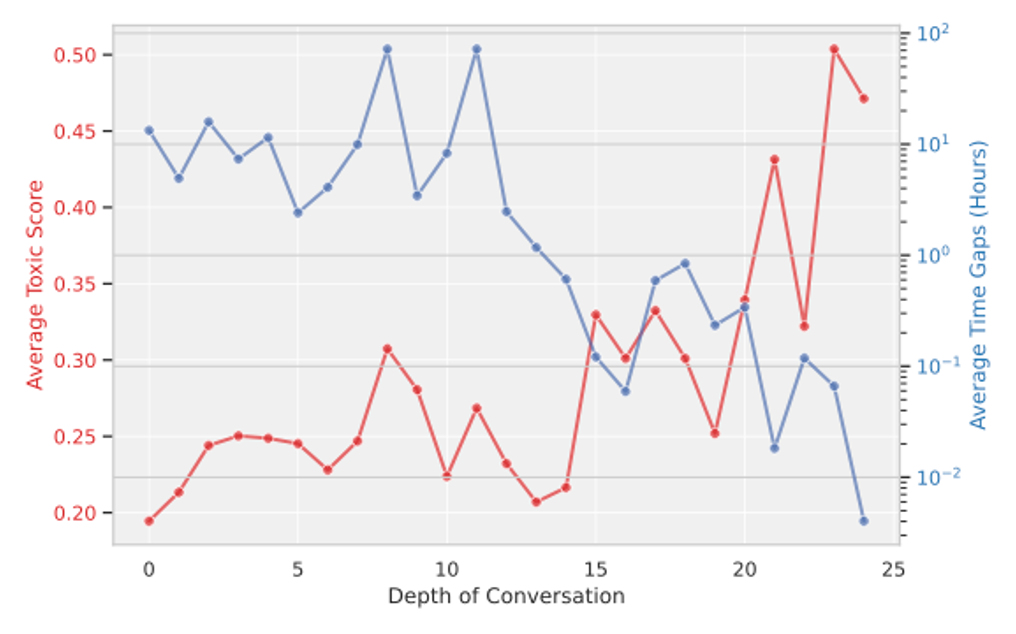

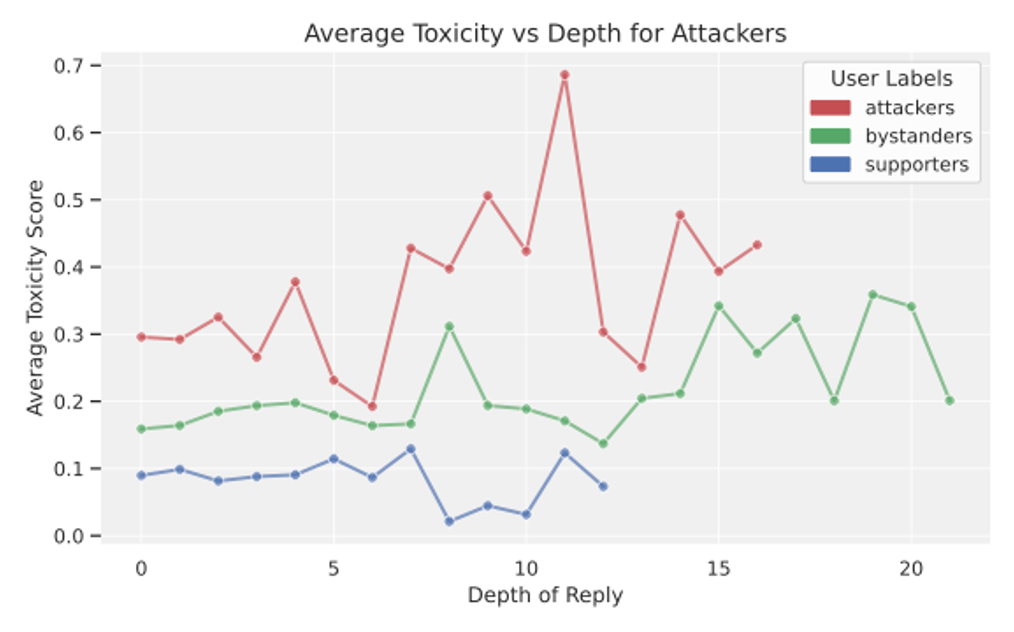

- Conversations Get Hotter and Faster (RQ4): As conversation threads get deeper (i.e., more replies), they become more toxic and the pace of replies speeds up (the time gap between replies decreases).

- Bystanders Get Sucked In (RQ4): Attackers’ toxicity appears to incite bystanders. We found that as conversations progress, bystanders become increasingly toxic. Supporters, meanwhile, tend to drop out of these deepening conversations.

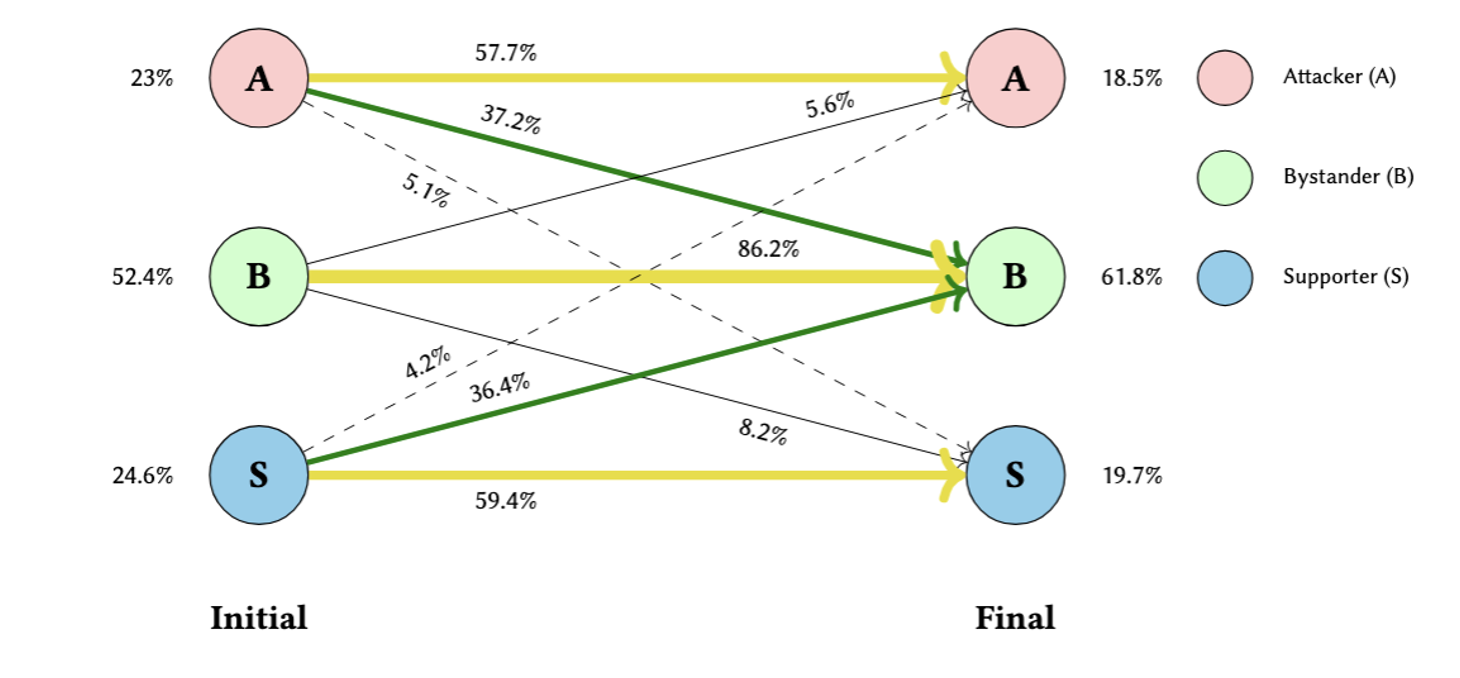

- Threads Lose Focus (RQ4): Deeper conversations also drift off-topic. We observed a large number of attackers (37.2%) and supporters (36.4%) eventually transition to becoming “bystanders”. This suggests they are no longer engaging with the journalist’s original post and may even be attacking each other.

Implications: Why This Matters

Our findings have direct implications for how social media platforms should handle online harassment:

-

Move Beyond Content Moderation: Moderating single toxic posts is not enough. Our work shows the problem is coordinated behavior. Platforms must shift from content moderation to behavioral moderation—detecting groups of users acting in concert.

-

New Tools for Journalists and Users: Journalists and users need better tools to fight back. This includes mechanisms to report coordinated attacks, not just individual accounts. Platforms could also intervene to automatically “slow down” conversations that are rapidly escalating in toxicity and pace.

Learn More

📄 Read the full paper: The Chilling: Identifying Strategic Antisocial Behavior Online and Examining the Impact on Journalists